Being a gamer, sometimes I’d get the urge to make my own adventure. I’ll get sick of the adventures I play, and feel that I can do it better. Of course, after I try my hand at it, I realize that it’s a lot of work, and requires a level of creativity that I don’t have. However, that didn’t stop me from at least learning the process of how to go about doing it.

Introduction

First, I’d like to describe the biggest newbie mistake for adventure game creation. Many people, including myself, start out first with writing the story. The story is what you remember most about a video game. You probably don’t remember much about the inner workings of the maze from that last game you played, but you definitely remember how your character overcame their ghost possession, and fought the coolest boss of the game. Naturally, since the story is the main reason you played an adventure game in the first place, many start making the game by making the story first.

Why is this a mistake? Because once you have the characters, setting, and plot written, you have severely limited yourself in what you can make for the rest of the game creation process. What if you find logical errors in the setting you created? For instance, it makes no sense to have a swamp right next to a desert right smack in the middle of the continent. Now you have to put it in a more logical place, and then change your story. You’ll be making story changes left and right so many times just to make it all functional that you’ll eventually give up. One story change could also force you to go back and change aspects of the setting that you’ve already built. This increases your amount of work exponentially.

What’s actually easier is to write a story around a world that’s already been built, especially if there’s already a predetermined path. “What reason can I come up with for why the character goes to the mountain after leaving the forest?” That is a lot easier to write a story around, and you’ll find you don’t change your story much.

So, with that in mind, here is the process to making an adventure game.

It comes in 4 phases: Dungeon, Over-chunks, Pathfinding, and finally Story.

Phase 1: Dungeon

First, you start with dungeon design. The best way to go about this is to pick a theme of some kind to design the dungeon around. Maybe it’s an element like air or fire (or the dreaded water dungeon that so many players hate). Or, maybe it’s more modeled after a cool human structure, like the foundry in Darksiders 2, or the silenced cathedral in Soul Reaver. Whatever dungeon you make, keep that theme in mind. Add the functionality to the rooms so that you can actually test them and move around through them. Perhaps some rooms are a logic puzzle, and others are a test of courage (i.e. clear the room of baddies). Whatever the case may be, build the dungeon skeleton first, and then make the event triggers to open doors or drop items for the user.

When all the dungeons are complete, you must also ask yourself whether or not you want to make “side-dungeons”. These are dungeons that aren’t integral to the plot at all (or maybe they are), and are designed for a very small side-track for the user. You can make them optional, wherein you can still beat the game without ever going through ‘em, and going through them is really for completion’s sake or extra reward. You could also make them mandatory, in which you want a really cool plot point to happen without forcing the user to go through too much hassle to get to it. Diablo 2 had side dungeons like this that were there strictly for the purpose of clearing it out and fighting a special named monster. Good loot, good exp. Whatever the case may be, now is the time to make these little levels.

Now, with all dungeons complete, you are now done with Phase 1

Phase 2: Over-chunks

This phase centers around the overworld pieces that lead into the dungeons. You don’t have to fully make the entire overworld… just the chunks that surround that dungeon entrance. If your dungeon is a moist and muddy kind of dungeon, perhaps you’ll put a swamp around the entrance. If it’s a fire-themed dungeon, perhaps you’ll want it at the bottom of a mountain volcano. Whatever you choose, make sure that the surrounding area makes logical sense around the dungeon theme it’s presenting.

Also, pick the type of dungeon entrance here… that is, do you want it to be a plain and bleeding obvious trail up to the dungeon entrance like Diablo 2? Or, maybe you simply wanna conceal the entrance a bit and make the user explore the chunk before they find it. Perhaps you want a logic puzzle like pressing switches or placing certain items into certain locations, or perhaps you want a test of courage by making the user fight a swarm of enemies first before the door to the dungeon becomes visible.

Take your time and just make something cool. Again, design the content itself first, then make the functionality for getting the entrance to open.

This phase also covers another kind of overworld chunk: upgrade stations. What I mean by upgrade stations are shops, or towns/villages… Or maybe you just want to make one central hub for the user to go to in order to upgrade, and it only exists in the “Dark Space” like in Illusion of Gaia. Maybe you want to make one big town designed to be the center of everything in the land, like Whiterun from Skyrim. Whatever the case may be, design the housing first, then design the people that will inhabit it. Don’t worry about what they’ll say, or what important info they’ll give just yet. Focus more on simply getting NPCs into the village, and making the upgrade NPC’s functional. Maybe you want the user to go through several new villages, each new one with slightly more powerful items…

Whatever the case may be, design these overworld chunks to your heart’s content. Don’t worry about connecting them just yet. We’ll figure all that out in the next phase.

With all the chunks complete, you can now consider phase 2 complete.

Phase 3: Pathfinding

Ok, NOW you can worry about putting the chunks together… or, whether you even WANT to put the chunks together. You have 2 decisions to make, and making these decisions will make you end up in 1 of 4 different outcomes. This part takes a while to explain, so it seems like a long process. All the choices in mind make this seem like a lot of work, but really this part is a 2 step process.

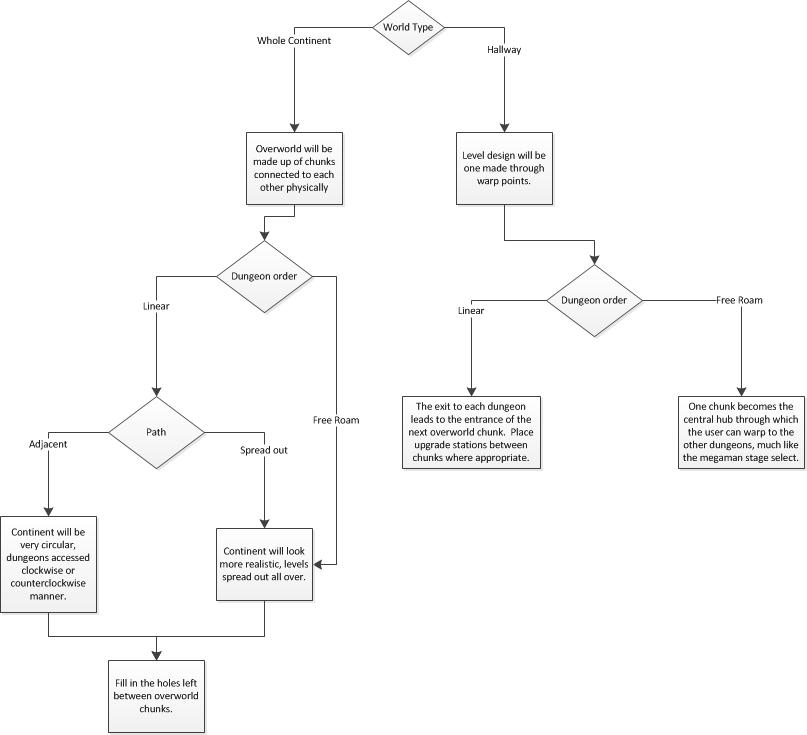

Here’s a flow chart to help illustrate the point.

First, you must decide what kind of world you want to make… Do you want the whole thing to be one big continent for the user to explore? Or, do you want it to be more like a giant hallway, like Final Fantasy XIII? If you choose the continent route, you’ll be giving the user more ability to explore the land, a much richer experience. The caveat is that it takes a hell of a lot longer to design. If you choose the hallway route, laying these levels out is very easy, and the user will navigate by way of warp points.

Your next decision is how you want the user to access these levels… Do you want it to be a linear progression, or a free-roaming one?

If you chose free-roaming, then the user can progress through the levels in whatever order they choose. If you made a hallway style, then the best way to go about this is to make a central hub that gives the user warp points to each overworld chunk. It functions exactly like the level select in megaman. Complete all the dungeons, then meet back at the center for the finale. However, if you made the overworld a whole continent, then you’ll have to make sure the continent is very circular. A long-line continent isn’t very explorable. This allows the user to explore their way on any part of the continent to find their chosen dungeon. The center of the circle will be the main hub town/village. When the user is through completing all the dungeons, again, they’ll meet back at the hub for the finale, or at least on directions to the finale.

If you chose linear, then the user progresses through the dungeons in a specific order. There is a bit of a science to this, actually. First of all, you don’t want the user to go through 2 dungeons of roughly the same type consecutively. Make the dungeon order varied so they get something different each time. It’s rather boring to go through a forest temple, followed immediately after by a swamp temple. A swamp is a less densely populated forest, but with more mud and water. Enough with the nature already! But, in trying to keep it varied, do not make the mistake of giving the user polar opposites. The reason why is because it’s pretentious. Don’t send the user from a sky temple to an underground temple, or send them from a fire temple to a water temple. Seriously… that’s not clever at all. There is, however, one exception to this rule, and that’s when going from fire to ice. Note, I said ice, not water. The reason is because the user will experience the world on a lower pyschological level as they progress through the game. After watching their character sweat like a pig for a whole dungeon, there’s nothing more refreshing than to go to an air-conditioned place. It’s almost a way of saying “too hot? ok, here, cool off in this other temperature extreme.” It does not work the other way around. Have you ever been out in the snow, and you come inside where it’s warm after nearly freezing to death? Well, did you want to simply get warm, or were you more in the mood to go into an oven? Most people would rather simply choose not be cold anymore instead of choosing to go into the oven extreme. But, when you’ve been suffering sweltering heat, do you not stick your head in the freezer? This is why it’s the only exception to the polar opposite rule.

Now, once you’ve selected the order in which you want the user to access these dungeons, you have to place them around based on how you chose to make your overworld. If you chose a hallway, then the best course of action is the make the end of every dungeon be a warp point to the next overworld chunk (be that an upgrading station chunk, or a dungeon entrance chunk). If you chose the continent style, then you have an additional decision to make. How linear do you want this to be? If it’s fully linear, then maybe you’ll want these dungeons to be placed right next to one another. The next dungeon, therefore, would be within the immediate vicinity of the last. This is incredibly lazy, but it doesn’t necessarily make it a bad game. The only time this is acceptable is if you’re making a very short game of about 4 dungeons or so… something the user is designed to complete in a couple hours. The other choice, of course, is to spread them out so the user has to travel across hell’s half acre every time they want to go to the next dungeon. Try to spread these chunks out on a continent where the landscape makes the best sense on an actual continent. Be realistic… Don’t stick a swamp next to a desert, and don’t put a forest in the center of the continent where they’d never receive any water from the coast. Once all the chunks are laid out the way you like them, you’ll need to fill in the holes between the chunks. Come on, after phase 2, there’s no way you set these chunks up so that they’re easily interchangeable… so fill in the holes with more land of some kind… some way of making a smooth transition from one region to another region.

Whew. Lot of explaining, isn’t it? Well, while this section looks long on paper, in practice it’s kinda short. Really, this is just finding out how you want your chunks laid out. Once laid out, you have to connect them, either through warp points or through physical land for the user to have to travel over. With this part done, you have now completed phase 3, and you can consider deploying your game as an alpha build.

Phase 4: The Story

Ok, now you can implement the story. It’s much easier to come up with an explanation as to why the user is going to where they’re going, or if it’s not linear, then why the user has a choice as to where to go. Create explanations as to why they’re choosing to go to town before the next dungeon, or why they’re going to a specific dungeon over another in the first place. Maybe the antagonist of the game is there, so you have to chase him down only to find that your princess is in another castle. It’s much easier to write the story around an already made world than it is to make a world around an already made story.

Get as creative as you want. Remember, this is the part gamers will remember about your game… so you have to decide whether you want the gameplay to be more memorable (i.e. this game is a glorified arcade game) or whether you want the story to be more memorable. It’s up to you. With the story completed, and finale finally recognized, you have now completed phase 4. At this point, you may now release a beta build of the game.

Why a beta? If we’ve completed all phases, why can’t we just deploy it now?

Well, because technically you’re not done yet. You have to fix any bugs and minor details you missed. Take this time to accept any tester input on what’s broken, and go in and fix it. Go search around your dungeons or overworld, and see if there aren’t any aesthetics to tweak.

You can also take this time to make another dungeon, that is, an optional one. Or, maybe you just want to make an area for your player to have fun in, like a music playing minigame or something. I guarantee you in Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, that Bombchu bowling alley and shooting range were afterthoughts. You could also spend the time to make something that just looks aesthetically pleasing… like an underground fountain with a beautiful statue to gaze and marvel at.

This part of the process doesn’t really get a “phase” in my mind, since all you’re really doing is tweaking and fixing what you’ve already done… You’re not really creating anything new or integral to the game. Maybe, if you make a new dungeon, but again, that dungeon would be completely optional… accessible only through a special warp point or something.

Then… then when all tweaks, fixes, and added superfluous content has been added, you may now package your game up as 1.0. You may release future iterations of the game with more bugs fixed (because let’s face it, people aren’t going to find everything at first). You could also release expansion packs that either change the content of the already made game, or simply add new places to explore. Build those in the exact same fashion you built this game.

Closing Thoughts

All in all, this is the process that works, and many game developers follow this path. Most adventure game makers have a whole team that can work on these pieces in tandem.

The whole point of writing down this process is to explain how daunting writing an adventure game actually is. I didn’t include the parts about game mechanics and such, because that has no relevance to this process at all. No game mechanic will make you detract from this process in any way.

So, in conclusion, making an adventure game is no trivial task, and requires lots of time, thought, testing, and aesthetic creativity. If you’ve got what it takes, then go for it. If you don’t, then let this process stand as a testament as to why you don’t want to bother. I personally can’t stay motivated long enough to follow through with this process. I’d need to be on a team of people who all share that drive so I can feed off of that energy. I’m actually not all that creative aesthetically, but functionally, I can make anything work, so I’d be a great event trigger writer or a tester.

I hope this guide helps some get their acts straight on designing games, or stops those who don’t realize they’re in way over their heads before they’ve invested too much time and money on it.